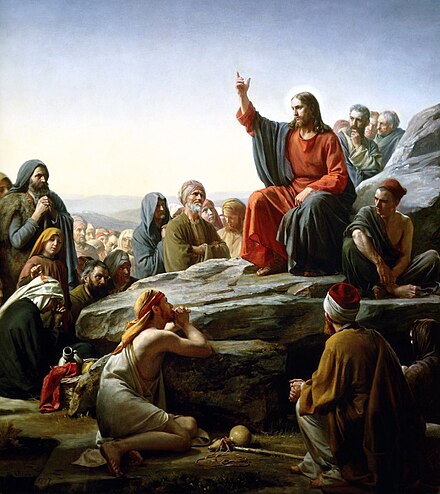

Bloch-SermonOnTheMount.

(Image by (Not Known) Wikipedia (commons.wikimedia.org), Author: Author Not Given) Details Source DMCA

Duluth, Minnesota (OpEdNews) December 11, 2019: The new 425-page book ambitiously titled The American Canon: Literary Genius from Emerson to Pynchon, edited by David Mikics of the University of Houston (Library of America, 2019) features a selection of Yale's later literary critic Harold Bloom's writings over the years about certain American literary geniuses. However, the dates of the original publication of each selection is not indicated in the book. But the opening selection about "Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803-1882)" (pages 13-38) has been updated to include passing discussion of President Donald Trump (pages 14, 22, 23, and 24).

I have discussed Bloom's updated essay about Emerson previously in my OEN article "Harold Bloom on the American Religion of Self-Reliance" (dated November 26, 2019):

But I now want to revisit Bloom's updated essay about Emerson and discuss it a bit further in the present essay. In doing so, I hope to clarify certain points in my previous OEN article.

After some introductory remarks, Bloom then quotes the following passage from Emerson: "'That is always best which give me to myself. The sublime is excited in me by the great stoical doctrine, obey thyself. That which shows God in me, fortifies me. That which shows God out of me, makes me a wart and wen. There is no longer a necessary reason for my being'" (quoted on page 14).

Now, when I was in the Roman Catholic religious order for men known formally as the Society of Jesus (known informally as the Jesuit order), I learned that Jesuit spirituality is based on a sense of God being in each person somewhat similar to what Emerson says here about "God in me." In Jesuit spirituality, the Jesuits have a motto about finding God in all things, which is a bit different from what Emerson says here about "God out of me." But the Jesuit motto is supposed to direct Jesuits to engage in careful discernments of spirits within their psyches and thereby help them in their conscious decision making.

For further discussion of ancient Stoic thought, see Troels Engberg-Pederson's book Cosmology and the Self in the Apostle Paul: The Material Spirit (Oxford University Press, 2010). Like the ancient Stoics, Engberg-Pederson himself hold the materialist philosophical position, but I hold the non-materialist philosophical position.

For further discussion of the apostle Paul in light of the non-materialist philosophical position, see M. David Litwa's We Are Being Transformed: Deification in Paul's Soteriology (Walter de Gruyter, 2012).

For an accessible discussion of the non-materialist philosophical position, see Mortimer J. Adler's book Intellect: Mind Over Matter (Macmillan, 1990).

Now, as Bloom continues his survey of Emerson's life and thought, he says, "On October 28, 1832, Emerson's resignation from the Unitarian ministry was accepted (very reluctantly) by the Second Church, Boston. The supposed issue was the proper way of celebrating the Lord's supper, but the underlying issue, at least for Emerson himself, was celebrating the self as God" (page 18).

Now, in both Western and Eastern Christianity, there has long been a tradition of thought about God within the human person's psyche being manifested in what is known as deification. See, for example, A. N. Williams' book The Ground of Union: Deification in Aquinas and Palamas (Oxford University Press, 1999). For earlier patristic sources, see Norman Russell's book The Doctrine of Deification in the Greek Patristic Tradition (Oxford University Press, 2004).

As Bloom continues his survey of Emerson's life and thought, he says, "Emerson's fantastic introjection of the transparent eyeball as bodily ego seems to make thinking and seeing the same activity, one that culminated in self-deification. Emerson's power as a kind of interior orator stems from the self-deification" (page 19). In short, Bloom is here interpreting Emerson's imagery and verbal expressions as tantamount to self-deification.

Now, as a reasonably well-informed but heterodox Jew, Bloom undoubtedly knew that Antiochus IV (born in c.215 B.C.E.; reigned 175-164 B.C.E.) had declared himself to be a god manifest ("Epiphanes"), a form of self-deification. But Bloom is not suggesting that what he interprets as Emerson's self-deification is as explicit as Antiochus IV's declaration about himself.

In light of the patristic and medieval Christian traditions (Western and Eastern) of thought about deification, I have no serious problem with interpreting Emerson's experience as a form of deification. However, as he manifests his own subjective sense of his own experience of a form of deification, I have certain reservations about Bloom's characterization of those manifestations as tantamount to self-deification.

Nevertheless, M. David Litwa (Ph.D. in religious studies, University of Virginia, 2012) of the Australian Catholic University in Melbourne reminds us of the bewildering ways in which self-deification was manifested in his 2016 book Desiring Divinity: Self-Deification in Early Jewish and Christian Mythmaking (Oxford University Press).

(Note: You can view every article as one long page if you sign up as an Advocate Member, or higher).