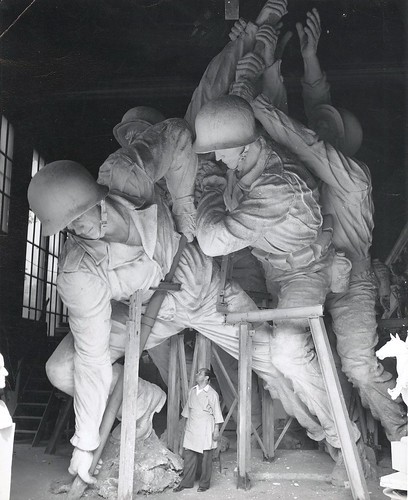

De Weldon and Marine War Memorial, circa 1954

(Image by Archives Branch, USMC History Division) Details DMCA

Quite aside from their intended symbolism, statues and memorials can have a secret unobserved or little known to passersby. In Florence, Italy, the famous statue of David is cross-eyed. Rodin's "The Thinker" has his elbow on the opposite knee. Buried in the recess of the Washington Monument's cornerstone are dozens of items including a bible, several atlases, some reference books, guides to Washington DC and the Capitol, census records from 1790 to 1848, poetry, a copy of the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence.

In Arlington, Virginia, the Iwo Jima memorial honors six U.S. Marines (and thereby the entire Corps) who raised the flag on Mount Suribachi after a hard-fought battle to capture the island in World War II. The story goes, and the writer has it on the authority of a very senior USMC officer when they were both assigned to the Navy Department, that the statue has an extra limb. Seems the sculptor, Felix de Weldon, thought there was too much empty space in the finished composition and added a leg.

Of the 58,318 (2019 count) names engraved on the Vietnam Memorial, thirty-four are still alive and can visit the wall and see for themselves. Eugene J. Toni lost part of both legs when he tripped a land mine on a reconnaissance patrol in the mountain jungles west of Hue. He was mistakenly listed as dead when a wrong number was typed into a computer.

All thirty-four computerized Defense Department records at the National Archives have been acknowledged and corrected, but the names - engraved in chronological order when they died - cannot easily be erased from the highly polished black granite. The only way is if a panel cracked and had to be replaced from the store of extra blank granite purchased at the Memorial's inception. The living names are not included in the published, hard copy edition or on-line version.

Twenty years after returning from Vietnam, Toni told an Associated Press journalist: "I woke up one day and decided I didn't want to be a double amputee any more. I felt like a prisoner who wasn't getting any time off for good behavior."

He sought treatment for post-traumatic stress syndrome and "part of the treatment was that I went down to the wall," where he scanned through the alphabetized directory. Turning to the "Ts" to find an uncle he had never met, he found his own name.

In Cambridge, Minnesota, Andrew J. Hilden found himself on one of the touring wall replicas. Willard D. Craig, former Private First Class, was called by an aunt when his niece found his name. Darrall E. Lausch heard when a relative reported that he was on a list published by The Detroit News of those from Michigan who were killed in Vietnam. It is probable that some of the 34 have no idea at all that they are among the fallen on that somber, lustrous black granite.

One of the names evokes an especially sharp poignancy. Army Staff Sergeant Daniel P. Ouellette boarded his helicopter in Long Bihn, just north of Saigon, on the first day of his second tour in Vietnam, Friday, May 17, 1970. His aircraft was tasked to fly a courier carrying top secret documents, and on the way pick up and deliver passengers. For the final mission of the day the helicopter left the helipad shortly after 6PM. Just a few minutes later while flying at an altitude of 70 feet, the aircraft struck two steel cables. The impact cut the radio compartment cover in half. The cables then slid over the roof and cut the antenna, air vents and aircraft controls. The rotor blades shattered pulling the aircraft downward into the Dong Nai river vertically, nose first, and disappeared from sight .

Three bodies broke free of the wreckage on the river bed and floated to the surface.

One was Staff Sergeant Ouellette who was rescued by the Vietnamese, still alive. Fifteen minutes after the accident a US harbor tug boat arrived at the scene and picked up Ouellette. Ten crew and passengers were killed, their bodies (all in an advanced state of decomposition) were recovered by SP/5 Robert Bogison in his flotilla of armed PBRs*.

Following recovery from severe injuries Ouellette, the lone survivor, had no memory of what had happened to him. By some extraordinary bureaucratic gaff, he is one of the 34 individuals on the Memorial, still alive. For decades he lived traumatized and homeless on the streets of Boston unable to cope with life. Persuaded to seek help, his VA counselor suggested a visit to the wall, a common therapeutic procedure for Vietnam War-related trauma victims. But when Ouellette saw his name up there along with the others aboard with him and the date of their death, he broke down completely.

Attempts by media and others to find him have failed.

*Patrol Boat River

Special thanks to Robert Bogison for allowing use of his pre- publication memoir, Up-Close & Personal: In-Country, Chieu-Hoi, Vietnam, 1969-1970 (2019)