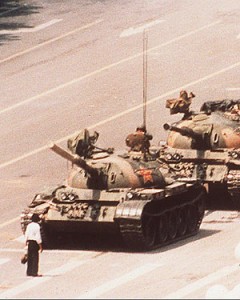

| It was 20 years ago today that the Chinese "People's" Army opened fire on thousands of Chinese people gathered in Beijing's Tiananmen Square. They -- for the most part university students -- were there in solidarity, supporting each other in the belief that the government was considering the easing of the totalitarian strictures that had, since before and after Mao's revolution, choked to death all attempts at liberation, whether it was artistic, holistic, political, or spiritual. The gathering began in mid-April and was sparked by the death of pro-democracy official, Hu Yaobang, whom protesters wanted to mourn. By the eve of Hu's funeral, which was scheduled for 21 April, 1,000,000 people had gathered in Tiananmen Square. The people in the Square knew they were safe. The People's Liberation Army would never, ever shoot at citizens. It was unthinkable. Right up until the moment the bullets began ripping into the crowd killing hundreds, wounding thousands -- the real numbers will never be known -- they were certain they were safe. I sat in front of a television for days leading up to the killing, transfixed by what appeared to be the first peaceful revolution I had ever witnessed. It was impossible not to watch. The joyful expectation of freedom was on the face of every person on whom the cameras from CNN focused. I felt an empathy entirely out of proportion, given the life I had led and my assumptions of the lives lived by the people whose faces floated in and out of camera range. And I was utterly confused by my feelings. How could I feel empathy with people changing their history when I had never experienced that sort of profound power myself? I watched their joy, their dedication to the monumental change about to occur because of their insistence on a peaceful and total revolution. When I saw that the students from the Central Academy of Fine Arts had carved and erected the "Goddess of Democracy," in the Square -- her right arm holding aloft a torch of liberation -- I cried. Wept. In that moment I could not understand why I felt the way I did on seeing that statue, so similar to my own Statue of Liberty in New York harbor. I still cannot find the exact words. When the man holding the shopping bag? briefcase? gym bag? stood in front of the approaching column of tanks not 24 hours after the slaughter began I knew I was seeing perhaps the only true hero I would ever see, a man of such immense courage, I again wept. Selfishly, I wanted simply to stare at him forever. I wanted to burn into my consciousness the image of this man forcing massive Chinese "type 59″ tanks to turn this way, then that, trying to get around him, trying to continue on their way to more death and destruction, yet there he stood, trying to block the way of these destructive behemoths with his own body, alone. The protests against Chinese Fascism lasted seven weeks, from Hu's death on April 15 until the Chinese Army cleared Tiananmen Square on June 4. Each day that CNN provided video tape -- until they were forced to stop their transmissions by the government, I watched. The last bit of video showed the CNN crew in their hotel room being forced to turn off their equipment. The screen on my television went dead, filled with the electronic "snow" that always signaled trouble. Then it went to black. The empathy I felt with the students, the sadness of realizing their efforts were meaningless; the horror that ripped through me the moment I learned of the killings, were made even more intense because here in the States in the late 80s, it was clear our own experiment with democratic self-governance was ending, washed away in the onrushing red tide of corporatism and the daily news reports of the atrocities committed by two of our presidents, Bush One and Reagan, in what was referred to as the Iran-contra affair. According to Wikipedia, unlike the Cultural Revolution, about which people can still easily find information through government-approved books, magazines, websites, et cetera, this topic is forbidden by the government and accordingly generally cannot be found in mainland Chinese media or websites. The official media in mainland China views the crackdown as a necessary reaction to ensure stability. As the incident is not part of any education curriculum in China, usually Chinese youth born after the crackdown learn of the protests from hearsay, family and foreign media. Every year there is a large rally in Victoria Park, Causeway Bay, Hong Kong, where people remember the victims and demand that the CPC's official view be changed. In 2008, this vigil was reported for the first time in the mainstream Chinese press, but was attributed to be in support of the victims of the recent earthquake in south-east China, and no mention of Tiananmen Square was made. To the students, workers, and intellectuals who died that June night in Tiananmen Square, I swear I will never forget the honor, courage, and, yes, poetry you offered the whole world. Your actions might have been, could have been, the spark that ignited the goddess's torch, a spark that would have spread across the planet. But, the spark was just that -- a soft glow on a warm June night that died in a cascade of gunfire. |

Tiananmen |

|

|

Rate It | View Ratings |

Mike Malloy is a former writer and producer for CNN (1984-87) and CNN-International (2000). His professional experience includes newspaper columnist and editor, writer, rock concert producer and actor. He is the only radio talk show host in America to have received the A.I.R (Achievement in Radio) Award in both (more...)

The views expressed herein are the sole responsibility of the author

and do not necessarily reflect those of this website or its editors.

OpEdNews depends upon can't survive without your help.

If you value this article and the work of OpEdNews, please either Donate or Purchase a premium membership.

STAY IN THE KNOW

If you've enjoyed this, sign up for our daily or weekly newsletter to get lots of great progressive content.

If you've enjoyed this, sign up for our daily or weekly newsletter to get lots of great progressive content.

To View Comments or Join the Conversation: