From New York Books

In Kim Stanley Robinson's anti-dystopian novel, climate change is the crisis that finally forces mankind to deal with global inequality.

The prolific science-fiction writer Kim Stanley Robinson, who is at heart an optimist, opens his newest novel, The Ministry for the Future, with a long set piece as bleak as it is plausible. Somewhere in a small city on the Gangetic Plain in Uttar Pradesh during the summer of 2025, Frank, a young American working for an NGO, wakes up in his room above a clinic to find that an unusually severe pre-monsoon heat wave has grown hotter still and more humid -- that the conditions outside are rapidly approaching the limit of human survival. Actually, conditions inside are approaching the same level, because the power has gone out.

Frank manages to get a generator going and opens the doors of the NGO's offices to seven or eight extended families, who cram themselves into the few rooms where creaking air conditioners knock the fatal edge off the heat. But then local thugs take both the generator and the AC unit at gunpoint. The temperature inside and out approaches 108 degrees Fahrenheit; the humidity is 60 percent. People start to die, and their bodies are taken up to the roof and left there. As night falls, Frank goes with some of the survivors to the shallow lake in the center of the city and they submerge themselves in the water, hopeful it will help them survive. It doesn't -- the lake water, too, is above body temperature, and as thirsty people drink it,

"hot water in one's stomach meant there was no refuge anywhere". They were being poached."

People were dying faster than ever. There was no coolness to be had. All the children were dead, all the old people were dead. People murmured what should have been screams of grief.

Frank survives, barely, with a lifelong case of PTSD: "Any time he broke a sweat his heart would start racing, and soon enough he would be in the throes of a full-on panic attack." Even a job he gets in the UK in a meat-processing plant with refrigerated rooms is not enough to keep the terror at bay. Nor the guilt, nor the anger, which become plot points of sorts in this sprawling novel. An uncountable number of Indians died in the heat wave he survived -- perhaps 20 million. In the book, it marks the effective starting point of humankind's effort to deal realistically with climate change.

And such a heat wave is not unlikely -- in fact, it is all but guaranteed. We came pretty close in California in September, when temperatures even in communities near the ocean like San Luis Obispo hit 120 degrees Fahrenheit, albeit at a lower humidity. Over the last few years we've seen record-breaking combinations of heat and humidity in Middle Eastern cities -- the heat index has approached 160 degrees Fahrenheit in places like Dhahran, Saudi Arabia, and Bandar, Iran. The latest research -- some of it published last summer -- indicates that such heat waves will become steadily more common. As the decades pass, a belt across India, Pakistan, and the North China Plain will see temperatures past the survival point for days and weeks at a time. The heat wave that killed tens of thousands in Europe in 2003 is only a foretaste.

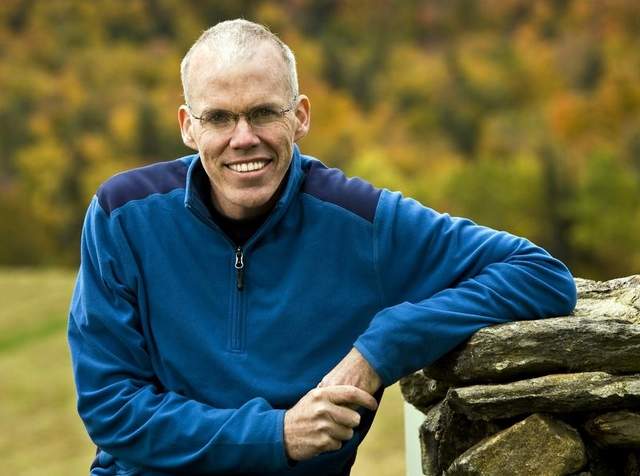

In taking on heat and glacial melt and fire, Robinson is writing more realistic fiction than most contemporary novelists, for whom the physical world remains a backdrop for more interior stories. We are entering a period when physical forces, and our reaction to them, will drive the drama on planet Earth. We are lucky to have a writer as knowledgeable, as sensible, and as humane as Robinson to act as a guide -- he is an essential authority for our time and place, and our deliberations about the future will go better the more widely he is read, for he is offering a deeply informed view on what are quickly becoming the great questions of world politics. The New Yorker once asked if Robinson was "our greatest political novelist," and I think the answer may well be yes. He's not trained as a scientist, but he's so up on the literature that he's usually three or four years ahead of the news, and not just in the US -- his sense of the Earth's political currents, including the rise of China and India, runs deep.

Which is interesting, because Robinson first made his mark writing about a different planet. His Mars trilogy, published in the 1990s, won every science-fiction award there is. (Robinson writes long books, and they often come in groups of three.) That story begins at almost the same time as The Ministry for the Future does: a group of a hundred earthlings takes off in 2026 to colonize Mars, as conditions on their home planet begin to deteriorate. It is an epic tale of the technological effort required to "terraform" Mars -- to make it habitable for humans by, say, drilling deep holes to release subsurface heat, and exploding nuclear weapons in the permafrost to start producing flowing water. Robinson's scenarios are precisely what NASA engineers were thinking through back then: that it was only a matter of time before we colonized the red planet. But in truth the technology is secondary -- his true interest, then and now, is more in political science than in science itself.

The Mars trilogy is really an exercise in asking how humans could, would, and should settle an uninhabited place: how, given a blank slate, we might work out our divisions and create a society that could survive and thrive. With a Mars colony as a setting, Robinson needed to deal with only a scattered few people on an empty world and had room to address questions of human nature, human organization, and human agency that are harder to deal with on the messy, crowded, historically contingent world we actually inhabit. His careful thought in those early novels has paid off in the years since; the conceptual seedlings he nurtured on Mars he has transplanted back on Earth in his more recent work, culminating in The Ministry for the Future, which may serve as his ultimate account of how to set our Earth on a workable course.

Before diving in, however, it's worth noting why Robinson has mostly left space behind. In the decades since the Mars trilogy appeared, the science has made it clearer that we're not going to easily spread out into the cosmos. The visions of Jeff Bezos and Elon Musk notwithstanding, even colonizing Mars will be much harder than originally envisioned by the writers of space operas and the NASA planners in the halcyon post-Apollo days -- among other things, NASA probes have discovered that the red planet is carpeted in a soil containing toxic perchlorates, so you'd somehow have to decontaminate the planet before you started doing anything grander.

It has also become clear that the distances involved in interstellar travel effectively preclude colonization outside the solar system: everything from the effects of radiation to the lack of genetic diversity in any "ark" that we'd send into space would amount to crippling obstacles. As Robinson has said:

"There is no Planet B, and it's very likely that we require the conditions here on earth for our long-term health. When you don't take these new biological discoveries into your imagined future, you are doing bad science fiction."

(Note: You can view every article as one long page if you sign up as an Advocate Member, or higher).