This piece was reprinted by OpEd News with permission or license. It may not be reproduced in any form without permission or license from the source.

Aspasia, beloved mistress of the ruler Pericles (495-429 BCE), likewise was tried for impiety, but his pleas saved her.

Diagoras of Melos (5th century BCE) was sentenced to death as a "godless person," but escaped into exile.

Anaxagoras (5th century BCE) was prosecuted for saying the sun and moon are natural objects, not deities. He also fled Athens.

Protagoras (485-415 BCE) wrote that it's impossible to know whether gods exist. Charged with impiety, he tried to escape to Sicily, but drowned at sea.

Xenophanes (560-478 BCE) joked that if oxen, lions and horses could envision gods, they would make them look like oxen, lions and horses.

Even the mighty Aristotle (384-322 BCE) was accused of doubt, and fled Athens.

Others charged included Theophrastos, Alcibiades and Andocides.

In the play Bellerophon by Euripides (484-406 BCE), the main character says:

"Doth someone say that there be gods above? There are not. No, there are not. Let no fool, led by the old false fable, thus deceive you."

In the play Knights by Aristophanes (448-380 BCE), another scoffs:

"Shrines! Shrines! Surely you don't believe in the gods. What's your argument? Where's your proof?"

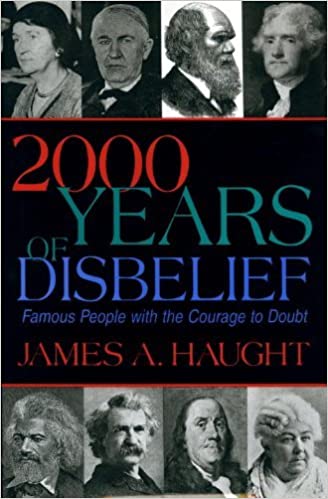

All this skepticism arose in Ancient Greece. It was suppressed under Christianity in the Dark Ages, but sprang back in the Renaissance, the Enlightenment and the Age of Reason to live in modern scientific times.

(Note: You can view every article as one long page if you sign up as an Advocate Member, or higher).