Evening in the Jungle, Calais- Author

It seems impossible to pass through the fencing, the walls, the buffer zones and tunnels, but they do. There is something quietly quixotic about them as they try night after night. They embody the indignity of the 'have nots' against the 'haves', of human folly and yet at the same time hope. Has England become an obsession or does it contain some hidden street paved with gold? In the UK a refugee will receive five pound twenty a day, he will rely on food banks and suffer hardship but he is safe and that is worth its price in gold. After all, these people have journeyed from Eritrea, Afghanistan, Iraq, Syria, Libya and many other countries escaping brutal dictators and war. The English channel will not thwart them. In fact, during the night, the Syrian corner of the camp is lit up by a twelve foot flame seen by all. Initial fears that the shanties are ablaze are dispelled by the sound of whooping and singing. One of their brothers have made it to London. How? God knows, but the story is a testament to human resilience.

If Ammar makes it he has to convince the UK authorities that he has arrived with out knowing that he has been transiting through other European countries. More than that, he hopes that he hasn't been snapped up by one of the men working for the British intelligence services. Junglists are aware that many people at the camp work for the intelligence services because friends who have made it, have seen them at Dover police station fraternising with the officers. In truth, the security services have no choice. The Jungle is a security concern, especially in the wake of Paris and Brussels.

For Ammar, though, there are easier ways. He can seek asylum in France and then be put in Camp Salaam with its the pristine white containers and warm showers. But Camp Salaam feels like prison. They are kept there till their application is processed. Those that apply seem to be from the Francophone world so France is the most logical destination to seek asylum. In any case, they probably do not have any finger prints any where else in Europe. If they do, the Dublin Agreement III requires that the host country send them back to the first European country of entry. They will be deported from that camp and find themselves in Serbia or Greece. This is what the Junglists fear the most; being sent back. These refugees prefer the freedom outside of Camp Salaam, but the freedom of the Jungle is fused with the ever pervasive smell of human excrement and rank green water that gather in pools where brown rats have pool parties.

***

The Prophecy of Micah- Author

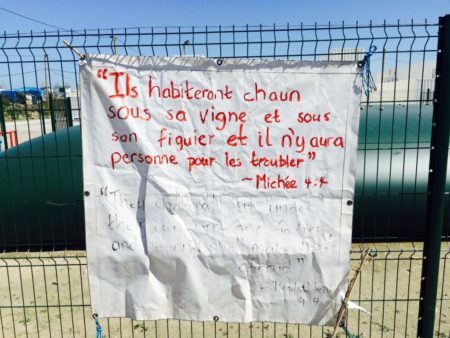

Even though there is no capo in the camp, somehow things just fall into place. There is an anarchic sort of order here. One would expect the Junglists coming from such different cultures to be at each others' throats. But they behave very much like the prophecy of Micah, in the Old Testament, whose message is displayed in the camp for everyone to see:

"They shall all sit under their own vine and the fig tree and no one shall make them afraid."

Each community rests with their own. Each area is loosely identifiable. The Kurdish area has its flag fluttering red, white and green with the sun in the middle. The Afghans with black, red and green, the Sudanese more so for their practice of playing dominoes at all times of the day and burning incense.

The Syrians have no flag, neither the flag of Assad, nor the flag of the revolution flutters here. Most are barely men, sons of farmers who joined the uprising in their teens. It is hard not to love their generous spirit. They continuously fill your cup with coffee and tea. Many of them, as Umm Sulaiman says, hail from "Der'aa al-manquba"- "The city of Dera'a that is riddled with holes". It is the same city where the Syrian uprising began.

And yet, after five years, the revolution, at least from the Jungle, is hard to discern. In April 2013, the former Syrian Brotherhood Spokesman Zuheir Salem warned: "If Assad stays, you will see Europe flooded with fifteen million Syrian refugees." This is coming to pass. But Syrians do not unquestioningly apportion all the blame on the regime or its barrel bombs for the failure of the revolution. The rebels have had five years to cobble together a credible opposition and they have failed miserably. Syrians can't quite figure out why the revolution has failed. Some of the refugees say, without providing a shred of proof, that DAESH or ISIS is the creation of Shi'ite Iran with its head quarters in London. Others blame America and others blame themselves. Abu Umar from Idlib, pulls on his cigarette, sitting in his tidy hut and says: "Is there any government in the world that isn't oppressive now? Is it not the case that my cousin took the bribe, my brother tortured prisoners, my neighbour did such and such? We are given rulers that we deserve as the Quran says." Abu Umar believes that Syria's solution can only be solved once Syrians achieve inner piety.

The men from Dera'a celebrating- Author

But though they have no common flag, there are still strong kinship ties. Umm Sulayman, for instance, has no one. She looks like one of those Okies from 1930s America. Her children, one six year old boy and one two year old girl, play barefoot in the sand. Her husband was killed by the Assad regime and now she relies on her countrymen and the Jungle to support her. There are men like Jamal, an engineer from Newcastle, who ensures that her camper has enough gas, that they are fed and that her two children are looked after. Like the Okies who dreamt of going to California, she hopes to join her family in England. But in truth; there is no possibility of that. The lawyers can't help her, the Dublin Agreement III again is the problem. If she arrives in the UK her application for asylum will fail. She has to convince the immigration officers that she did not stop in any other country. If her story is not airtight the immigration officers in Lunar house, Croydon, will put holes in it.

In the camp, religion does play a part in ordering the lives of the Junglists. One greeting of salaam, one prayer to protect their family breaks down barriers and suspicion. There is one church and seven mosques. Masjid al-Mouhajer is the one the Syrians go to. The central mosque is the Umar mosque, a tarpaulin structure, set up in order to unify and give a sense of solidarity amongst the Junglists. Umar mosque was the brain child of a Syrian, Abu Omar, Jamal and other imams who came together and encouraged the men to set up a mosque for the sake of fraternity. It is this mosque that helps to diffuse the tensions that flare up in the camp periodically. The mosque is led by Imam Katibullah, a Pashtu with piercing grey eyes who speaks Arabic, walks the camp in his black shawl, panjabi and Pakhool, and gives pastoral care to all and sundry and seems loved by the camp.

At evening prayer, it is as if all the ills suffered by the Muslim world gather; there stands its past glories and its present misery and its future hopes, all united behind the Afghan Imam, Katibullah. Watch the men pray and raise their hands to their Maker and you see that some pray for paradise and some, dare one say it, pray to England, and some pray as if tonight will be their last day on Earth. And sometimes it really is their last day.

Whilst the politicians in Westminster wrangle over what is to be done, the people of England show the same generous spirit that accepted refugees in the past, whether Hugenot Protestant, Jew, Pole or East African. This is acknowledged by the Junglists. One guesstimate puts it that ninety percent of the volunteers are from Britain. They donate disused caravans that go to the most vulnerable. There are makeshift medical clinics offering primary care, youth clubs, legal advice and other services, all funded by these volunteers. Names like Sophie, Claire, Iona are mentioned with intense reverence and affection and, though some of these volunteers do not believe in saints or God for that matter, they are trusted like saints and many children are given to their care. But there is also a sense that whilst these men and women give to the refugees, they too seem to gain something. It is hard to tell as to exactly what that is, but as Jamal says: "they cannot go back to their societies and live normally after the Jungle." Whilst some volunteers come to experience the anarchic freedom, the hospitality of the men with nothing, perhaps even to savour the cannabis, you get the sense that they too maybe searching for something.

(Note: You can view every article as one long page if you sign up as an Advocate Member, or higher).