Cross-posted from Consortium News

For most of the last five decades, it has been assumed that the Tonkin Gulf incident was a deception by Lyndon Johnson to justify war in Vietnam. But the U.S. bombing of North Vietnam on Aug. 4, 1964, in retaliation for an alleged naval attack that never happened -- and the Tonkin Gulf Resolution that followed was not a move by LBJ to get the American people to support a U.S. war in Vietnam.

The real deception on that day was that Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamara misled LBJ by withholding from him the information that the U.S. commander in the Gulf -- who had initially reported an attack by North Vietnamese patrol boats on U.S. warships -- had later expressed serious doubts about the initial report and was calling for a full investigation by daylight. That withholding of information from LBJ represented a brazen move to usurp the President's constitutional power of decision on the use of military force.

Johnson had refused to retaliate two days earlier for a North Vietnamese attack on U.S. naval vessels carrying out electronic surveillance operations. But he accepted McNamara's recommendation for retaliatory strikes on Aug. 4 based on reports of a second attack. But after that decision, the U.S. task force commander in the Gulf, Capt. John Herrick, began to send messages expressing doubt about the initial reports and suggested a "complete evaluation" before any action was taken in response.

McNamara had read Herrick's message by mid-afternoon, and when he called the Pacific Commander, Admiral U.S. Grant Sharp Jr., he learned that Herrick had expressed further doubt about the incident based on conversations with the crew of the Maddox. Sharp specifically recommended that McNamara "hold this execute" of the U.S. airstrikes planned for the evening while he sought to confirm that the attack had taken place.

But McNamara told Sharp he preferred to "continue the execute order in effect" while he waited for "a definite fix" from Sharp about what had actually happened.

McNamara then proceeded to issue the strike execute order without consulting with LBJ about what he had learned from Sharp, thus depriving him of the choice of cancelling the retaliatory strike before an investigation could reveal the truth.

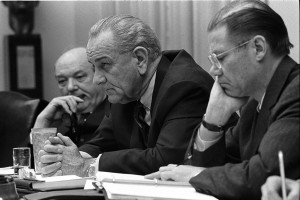

At the White House meeting that night, McNamara again asserted flatly that U.S. ships had been attacked in the Gulf. When questioned about the evidence, McNamara said, "Only highly classified information nails down the incident." But the NSA intercept of a North Vietnamese message that McNamara cited as confirmation could not possibly have been related to the Aug. 4 incident, as intelligence analysts quickly determined based from the time-date group of the message.

LBJ began to suspect that McNamara had kept vital information from him, and immediately ordered national security adviser McGeorge Bundy to find out whether the alleged attack had actually taken place and required McNamara's office to submit a complete chronology of McNamara's contacts with the military on Aug. 4 for the White House indicating what had transpired in each of them.

But that chronology shows that McNamara continued to hide the substance of the conversation with Admiral Sharp from LBJ. It omitted Sharp's revelation that Capt. Herrick considered the "whole situation" to be "in doubt" and was calling for a "daylight recce [reconnaissance]" before any decision to retaliate, as well as Sharp's agreement with Herrick's recommendation. It also falsely portrayed McNamara as having agreed with Sharp that the execute order should be delayed until confirming evidence was found.

Contrary to the assumption that LBJ used the Tonkin Gulf incident to move U.S. policy firmly onto a track for military intervention, it actually widened the differences between Johnson and his national security advisers over Vietnam policy. Within days after the episode Johnson had learned enough to be convinced that the alleged attack had not occurred and he responded by halting both the CIA-managed commando raids on the North Vietnamese coast U.S. and the U.S. naval patrols near the coast.

In fact, McNamara's deception on Aug. 4 was just one of 12 distinct episodes in which top U.S. national security officials attempted to press a reluctant LBJ to begin a bombing campaign against North Vietnam.

In September 1964, McNamara and other top officials tried to get LBJ to approve a deliberately provocative policy of naval patrols running much closer to the North Vietnamese coast and at the same time as the commando raids. They hoped for another incident that would justify a bombing program. But Johnson insisted that the naval patrols stay at least 20 miles away from the coast and stopped the commando operations.

Six weeks after the Tonkin Gulf bombing, on Sept. 18, 1964, McNamara and Secretary of State Dean Rusk claimed yet another North Vietnamese attack on a U.S. destroyer in the Gulf and tried to get LBJ to approve another retaliatory strike. But a skeptical LBJ told McNamara, "You just came in a few weeks ago and said they're launching an attack on us -- they're firing at us, and we got through with the firing and concluded maybe they hadn't fired at all."

After LBJ was elected in November 1964, he continued to resist a unanimous formal policy recommendation of his advisers that he should begin the systematic bombing of North Vietnam. He stubbornly argued for three more months that there was no point in bombing the North as long as the South was divided and unstable.

Johnson also refused to oppose the demoralized South Vietnamese government negotiating a neutralist agreement with the Communists, much to his advisers' chagrin. McGeorge Bundy later recalled in an oral history interview that he concluded that Johnson was "coming to a decision ... to lose" in South Vietnam.

(Note: You can view every article as one long page if you sign up as an Advocate Member, or higher).