Duluth, Minnesota (OpEdNews) November 1, 2021: Jennifer Schuessler's provocatively titled lengthy book review "What if Everything You Learned About Human History Is Wrong? In 'The Dawn of Everything,' the [late] anthropologist David Graeber and the archaeologist David Wengrow aim to rewrite the story of our shared past - and future" in the New York Times dated October 31, 2021, is about what is now known as Big History.

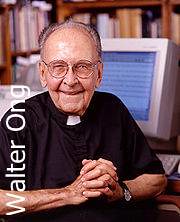

Years ago, before the term Big History became a fashionable term, the American Jesuit cultural historian Walter J. Ong (1912-2003) and the French Jesuit paleontologist Pierre Teilhard de Chardin (1881-1955) embraced what they both, in effect, conceptualized as a Christocentric version of Big History, albeit in the broad form of an outline of Big History.

Teilhard's writings about Big History were published posthumously in French - and then subsequently in English translation. Teilhard's most notable treatise about Big History is his posthumously published book The Human Phenomenon, translated from the French by Sarah Appleton-Weber (Brighton and Portland: Sussex Academic Press, 1999; orig. French ed., 1955).

Ong's earliest statement about the broad form of an outline of Big History can be found in his 1952 review-article about Marshall McLuhan's 1951 book The Mechanical Bride: Folklore of Industrial Man (New York: Vanguard Press) titled "The Mechanical Bride: Christen the Folklore of Industrial Man" in the journal Social Order (Saint Louis University), volume 2, number 2 (February 1952): pages 79-85. (The Christian editorializing expressed in the term "Christen" is Ong's, not McLuhan's. The young Canadian Marshall McLuhan [1911-1908; Ph.D. in English, Cambridge University, 1943] taught English between 1937 and 1944 at Saint Louis University, the Jesuit university in St. Louis, Missouri.)

In Ong's 1952 review-article, he has a subsection titled "Three Spheres of Being" (page 84). In it, he discusses the cosmosphere, the biosphere, and the noosphere (formed from the Greek nous, noos, mind). Ong credits "Father Pierre Teilhard de Chardin" with using the term noosphere (page 84).

When it comes to coining terms, I should also note here that Ong himself coins the term noobiology in the "Preface" of his 1981 book Fighting for Life: Contest, Sexuality, and Consciousness (Cornell University Press), the published version of Ong's 1979 Messenger Lectures at Cornell University - to distinguish the philosophical position that he is advancing in his 1981 book from the position that E. O. Wilson advances in his 1975 book Sociobiology: The New Synthesis (Belknap Press of Harvard University Press). Ong's term noobiology illustrates that the spirit of contest about which he writes in his 1981 book was alive and well in him.

In any event, in the "Preface" to Ong's 1977 book Interfaces of the Word: Studies in the Evolution of Consciousness and Culture (Cornell University Press, pages 9-13), he says the following in the first sentence: "The present volume carries forward work in two earlier volumes by the same author, The Presence of the Word (1967) and Rhetoric Romance, and Technology (1971)." He then discusses these two earlier volumes.

Then Ong says, "The thesis of these two earlier works is sweeping, but it is not reductionist, as reviewers and commentators, so far as I know, have all generously recognized: the works do not maintain that the evolution from primary orality through writing and print to an electronic culture, which produces secondary orality, causes or explain everything in human culture and consciousness. Rather, the thesis is relationist: major developments, and very likely even all major developments, in culture and consciousness are related, often in unexpected intimacy, to the evolution of the word from primary orality to its present state. But the relationships are varied and complex, with cause and effect often difficult to distinguish" (page 9-10).

Thus Ong himself claims (1) that his thesis is "sweeping" but (2) that the shifts do not "cause or explain everything in human culture and consciousness" and (3) that the shifts are related to "major developments, and very likely even all major developments, in culture and consciousness."

Major cultural developments include the rise of modern science, the rise of modern capitalism, the rise of representative democracy, the rise of the Industrial Revolution, and the rise of the Romantic Movement in philosophy, literature, and the arts.

In effect, Ong implicitly works with this thesis in his massively researched 1958 book Ramus, Method, and the Decay of Dialogue: From the Art of Discourse to the Art of Reason (Harvard University Press) - his major exploration of the influence of the Gutenberg printing press that emerged in the mid-1450s. Taking a hint from Ong's massively researched 1958 book, Marshall McLuhan worked up some examples of his own in his sweeping 1962 book The Gutenberg Galaxy: The Making of Typographic Man (University of Toronto Press).

Next in Ong's 1977 "Preface," he explains certain lines of investigation that he further develops in Interfaces of the Word. Then he says, "At a few points, I refer in passing to the work of French and other European structuralists - variously psychoanalytic, phenomenological, linguistic, or anthropological in cast" (page 10). Ong liked to characterize his own thought as phenomenological and personalist in cast.

However, as I like to say, Ong is not everybody's cup of tea, figuratively speaking. Consider, for example, Ong's own modesty in the subtitle of his book The Presence of the Word: Some Prolegomena for Cultural and Religious History (Yale University Press, 1967), the expanded published version of Ong's 1964 Terry Lectures at Yale University. His wording "Some Prolegomena" clearly acknowledges that he does not explicitly claim that his thesis as he formulated it in his 1977 "Preface" does "explain everything in human culture and consciousness" - or every cause -- but that the shifts he points out are "sweeping."

(Note: You can view every article as one long page if you sign up as an Advocate Member, or higher).