1. Power Distance Index (PDI)Let's unpack these terms.

2. Individualism

3. Uncertainty Avoidance Index (UAI)

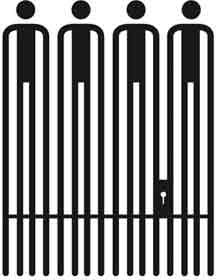

The first, Power Distance Index indicates that the French accept the fact that power is distributed unequally. It's an index of how far people will endorse their society's level of inequality. As Hofstede says, "anybody with some international experience will be aware that 'all societies are unequal, but some are more unequal than others'." By and large French people accept the inequalities in their society - or rather, have been crushed by their centuries-long experience of bureaucracy into such an attitude. So much for egalità �. It's been given up as a hopeless ideal.

Individualism is another factor where French culture scores high. This indicates how far each member of the culture looks out for each other, and is willing and able to help each other out. The high individualism quotient tells us that France is split up to a high degree into individuals, with any grand idea of "society" relegated to the dustbin. France is not really collectivist in its cultural thinking. Fraternità � too, then, has been effectively discarded. Or perhaps it would be better to say that it's been successfully stunted by the French governmental and cultural elite in Paris.

Uncertainty Avoidance Index (UAI) deals with a society's tolerance for uncertainty and ambiguity; it ultimately refers to man's search for Truth. It indicates to what extent a culture programs its members to feel either uncomfortable or comfortable in unstructured situations. Unstructured situations are novel, unknown, surprising, different from usual. Uncertainty avoiding cultures try to minimize the possibility of such situations by strict laws and rules, safety and security measures, and on the philosophical and religious level by a belief in absolute Truth; 'there can only be one Truth and we have it'. People in uncertainty avoiding countries are also more emotional, and motivated by inner nervous energy. The opposite type, uncertainty accepting cultures, are more tolerant of opinions different from what they are used to; they try to have as few rules as possible, and on the philosophical and religious level they are relativist and allow many currents to flow side by side. People within these cultures are more phlegmatic and contemplative, and not expected by their environment to express emotions.For comparison, here's a handy list on how different countries shaped up on the UAI. It should be fairly clear that freedom of thought - our most basic kind of liberty - has been junked. Goodbye libertà �.

That's an assessment of the French character. To recap: obviously we're not talking about uninformed national 'stereotypes' exactly, but attempts to understand and scientifically assess the cultural forces that act as a force in the lives of people in that region - whether they're French (in this case) or have come to live and work in that country from abroad. It's also an indicator of the sorts of attitudes that are helpful to have if a person wants to achieve power in that region. In that sense, it's simply a matter of social anthropology - a morally neutral description of a given people's culture.

But how did these attitudes come about?

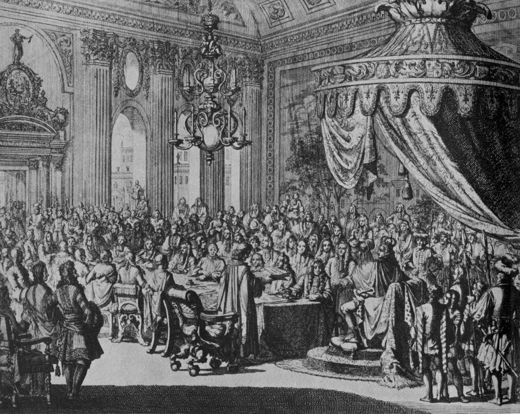

Let's go back a few years, to 1685. The Edict of Fontainebleau, perhaps more commonly known as the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes, marked the point when the King of France, Louis XIV, decided on a major change in the government of the country. By 1685, Louis was the most powerful monarch in Europe. His power was founded on his personal finances, which flourished precisely because the country was internally stable. A lot depended on the king's image: this was the still central point to which all eyes were directed; hence the propaganda about Louis as the 'Sun King'.

Louis marked the high-point of France's Ancien RÃ �gime. An elaborate theatricality pervaded Louis' court at his new palace of Versailles. Louis was widely understood as the embodiment of France. But there was one area where Louis was not the king, at least in his own mind. Some ninety years before, in 1598, the civil war in France - the Wars of Religion - had been brought to a close by Henri IV with the Edict of Nantes. This edict stated that it was permissible for a person in France to be either a Catholic or a Protestant. There was a degree of freedom of thought and religious expression. Sectarianism was now no longer regarded as a danger to the State.

Nevertheless, it had to be admitted, this new edict did run counter to the established custom after the Reformation of cuius regio, eius religio: as a citizen of some one particular European state, the custom arose in the aftermath of the Protestant Reformation that a citizen must conform to the religion of their monarch. But the civil war in France had been far too dangerous, and had endangered the security of the State far more than the actual existence of sectarians in themselves ever could. And so the Edict of Nantes was passed to end sectarian persecution, and allow the country to recover.

Louis' success by 1685 - financial, military and diplomatic - allowed him to reverse history. The 'problem' of sectarianism in France could now be dealt with by a firm decision and a strong hand. Now there would be a real unity: a pyramid of power, with the sacred king at the top. The mistake - for almost all historians see Louis' decision as an appalling act of misjudgement - was that Louis understood national unity in terms of uniformity or conformity.

An abiding idea here has to do with the theatre of power. Cultural historians have been fascinated with the elaborate way in which court life at Versailles was choreographed rather like an elaborate dance. There was a strict regimentation about it, because the central idea was to give form to the State at its very centre. This form would then act as a force which radiated out to the rest of French society. It was all play-acting of course, but taken very seriously by the elite of the time. We see something similar in the pomp associated with presidents and monarchs today - but Louis XIV's court was an extreme example of this sort of thing.

We all know what form is. This may seem to be going off topic, but let me quote a highly interesting observation from Susanne Langer, in her Introduction to Symbolic Logic, which actually clarifies a lot of what was going in the minds of those who took part in court life in France during this period - and in the minds of those who govern France today:

The meaning of 'form' is stretched beyond its common connotation of shape. Likewise, in the science or art of musical composition we speak of a rondo form, sonata form, hymn form, and no one thinks of a material shape. Musical form is not material; it is orderliness, but not shape. So we must recognize a wider sense of the word than the geometric sense of physical shape. And indeed, we admit this wider sense in ordinary parlance; we speak of 'formality' in social intercourse, of 'good form' in athletics, of 'formalism' in literature, music, or dancing. Certainly we cannot refer to the shape of a dinner or a poem or dancing. In this wider sense, anything may be said to have form that follows a pattern of any sort, exhibits order, internal connection.The maintenance of form can be approached in one of two ways:

First, you can outlaw anything which doesn't conform to your idea of 'good form'. And in a country like France, where appearances count for so much, this seems to be the way they're going - the pursuit of uniformity or conformity.

The second approach is the approach favoured elsewhere in Europe: encouraging diversity (or at least being comfortable with it) as a means of extending that good form beyond its current limits - in fact, creating further interesting patterns as the form of the thing develops. It's the difference between creating an exquisite objet d'art like a statue, immovable and inviolate, but essentially lifeless, and creating something more audacious, something which is alive. France has gone for the first option - something it clearly expresses in the extremism of its language policy, and the way it operated until Algerian independence in North-west Africa. National purity was seldom pursued so vigorously - and so pointlessly. It's as though there's an appellation d'origine contrà �là �e over the whole country: only that which comes from France is the genuine article. France has become contra mundum; it's France versus the rest of the world.

The matter is very much a religious one, despite the fact that the State formally separated itself from the Church in 1905. In the minds of the French, the year 1905 is very important. It marks the beginning of a conscious process of what's called laà �cità �. The word approximates more or less to 'secularism', but actually goes much further. It indicates a conscious push toward rationality in all things - and for that reason is linked back to the aims of the French Revolution. It has the same aims as the French Encyclopedists of the Age of Enlightenment who provided a good part of the philosophical momentum for the Revolution. French state-funded schools teach laà �cità � as a matter of course, and it's become ingrained in the public consciousness as a fundamentally correct approach to things. The principle of laà �cità � is a matter of political correctness, and is challenged in French circles at one's peril.

(Note: You can view every article as one long page if you sign up as an Advocate Member, or higher).